From darkness to light

We find Bruno Dufourmantelle in the studio where he lives, a stone's throw from the Odéon, as if moored to his canvases which, over time, have invaded him. Without chaos - a hundred or so large compositions, consigned with the utmost precision to 65 m2, is a performance in itself. Imperial, under the immense glass roof, his easel. Facing north. Absolute condition for the authentic light to reveal itself. A secret shared with the painters who preceded him here, Whistler, Gustave Doré and Yves Brayer. Bruno Dufourmantelle didn't always work here. It became his after his first wife, the late philosopher and psychoanalyst Anne Dufourmantelle, who tragically passed away in July 2017, relinquished it to him. Years before, she had chosen to live here, thinking of what she was losing by leaving this man - certain, then, that this rare space would be conducive to the unfolding of the work of the father of their two children.

We find Bruno Dufourmantelle in the studio where he lives, a stone's throw from the Odéon, as if moored to his canvases which, over time, have invaded him. Without chaos - a hundred or so large compositions, consigned with the utmost precision to 65 m2, is a performance in itself. Imperial, under the immense glass roof, his easel. Facing north. Absolute condition for the authentic light to reveal itself. A secret shared with the painters who preceded him here, Whistler, Gustave Doré and Yves Brayer. Bruno Dufourmantelle didn't always work here. It became his after his first wife, the late philosopher and psychoanalyst Anne Dufourmantelle, who tragically passed away in July 2017, relinquished it to him. Years before, she had chosen to live here, thinking of what she was losing by leaving this man - certain, then, that this rare space would be conducive to the unfolding of the work of the father of their two children.

Now the only atypical anchor point in a family that is no less atypical, this studio is the place of serenity rediscovered with Aude, the new dawn, the artist's gentle and brilliant companion. A painter for fifty years, he is exhibiting some thirty major works at the home of Amélie du Chalard, who has seized the opportunity to bring together in the beautiful Hôtel d'Aguesseau, now her "Maison d'art", the monumental canvases that have marked the life of this great loner. The prodigious drawings of the last two years, too - an unprecedented experience for him, "behind the scenes of his painting", as she puts it. A prolific body of work that obsesses the young woman "in an addictive way", and which she doesn't hesitate to compare to that of Monet or Rothko. "These canvases fascinate me by their meditative power as much as by the quality of their surface, the pictorial technique which has become extremely rare. Paintings and drawings, all Bruno's ambivalence and uniqueness is here. In the power as much as the gentleness, the poetry, the light of the glazes and the fastidious rigor, the unheard-of demands, the obsessive labor of the pencil...".

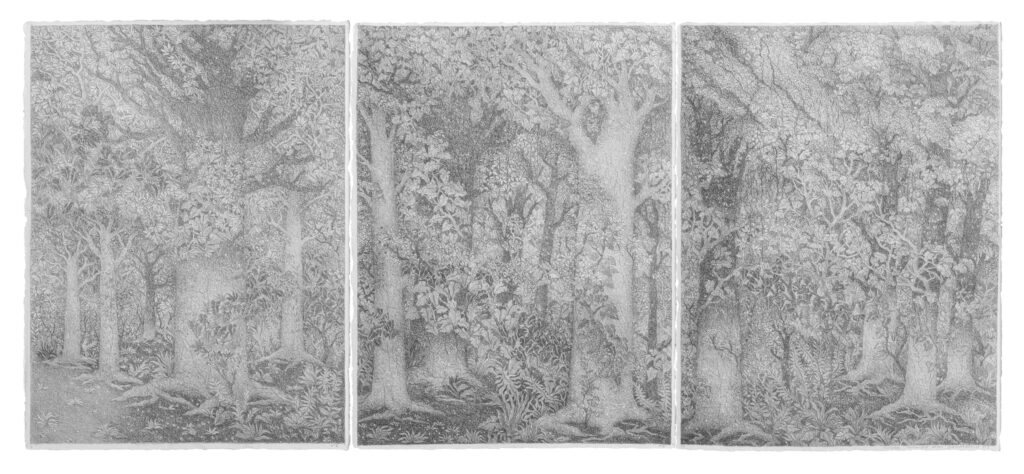

The nimble fingers of his left hand, guided by who knows what celestial threads, fascinate as we approach the Arches vellum where, from the upper right-hand corner, a new landscape in graphite emerges. "My totally unprecedented confinement with drawing began shortly before the Covid with Les Paysages inconnus, but it was in February 2020 that Les Forêts brisées (the series of drawings on show, editor's note) appeared, just as France was confining itself for the first time," observes the artist. "The starting point is multitude. That of the granite of northern Brittany, similar, from afar, to the human mass, up close, to the innumerable individualities, to our history... In these forests, I feel what humanity is going through. They are full of what we are collectively becoming. I always see a broken part. Like the branch on the ground, despite its apparent blossoms. That's today's world for me. Broken but suspended, uprooted and at the same time completely traversed by life..."

The nimble fingers of his left hand, guided by who knows what celestial threads, fascinate as we approach the Arches vellum where, from the upper right-hand corner, a new landscape in graphite emerges. "My totally unprecedented confinement with drawing began shortly before the Covid with Les Paysages inconnus, but it was in February 2020 that Les Forêts brisées (the series of drawings on show, editor's note) appeared, just as France was confining itself for the first time," observes the artist. "The starting point is multitude. That of the granite of northern Brittany, similar, from afar, to the human mass, up close, to the innumerable individualities, to our history... In these forests, I feel what humanity is going through. They are full of what we are collectively becoming. I always see a broken part. Like the branch on the ground, despite its apparent blossoms. That's today's world for me. Broken but suspended, uprooted and at the same time completely traversed by life..."

Her life, first and foremost. Devastated more often than not by the sudden loss of a mother, a brother, a cousin and, of course, Anne... "Painting is the best remedy for grief," he continues. Painting is the best remedy for grief," he continues. It disguises the precariousness of our lives, mocking mortals. As a substitute language, paintings beg the invisible to take us away from our finitude." A strange blend of rare clairvoyance and almost animal instinct, with his wildcat silhouette, piercing gaze and velvet voice, the man is never so animated as to find the immemorial words that will speak of the depth of the creative process. In anticipation of the period we were about to go through", he analyzes, "I abandoned large volumes and felt the need to seize the simplest, most archaic material available: a sheet of paper and a pencil. I worked here in a confined space, as if in a boat, tossed back and forth between desires for the infinitely small and the infinitely large, without the space or money to do anything else. An instinct, then, "because I never knew where I was going", and its share of trials, which have taken him, in an unprecedented way, at the age of 70, towards a precise infinity. A compelling challenge. The work of a slave. To drown the immensity of his sorrows. Where to fix one's mind, entirely turned towards the unknown, through a vertiginous exercise, without a net and necessarily fragmented - when space is so limited. The advantage of this paper," he says, "is that you can't cover it up or erase it. What's done is done. In fifty years of work, the paintings themselves have been made like that. No premeditation, no turning back. If there's prior construction, I can't work. When you jump into a void, the elastic holds you back. Without a rubber band, it's better not to have a floor. If there's no ground, you can go on...".

Thirty-two months of incessant work, with a lead (H or 3H) as the only compass for his days and nights. The result, according to Danièle Giraudy's expert eye, is "giant miniatures, Lilliputian jungles born of a cameo of a hundred values, from greys to blacks, where each plant element has its own vocabulary and color". Bruno Dufourmantelle admits: "You had to be unconscious to embark on such a crazy undertaking. Very sad too, but you wouldn't know it. Because it's not something locked up. It's a "journey towards"... Faithful to silence. Faithful to the light. To absence... I don't know if absence fades, but I do know that these drawings shed light on the paintings I've done all my life."

Even he is taken aback by the magnitude of this achievement. By the madness of these billions of seconds enclosed in an obscure confinement, similar and yet never the same, thanks to the drawing that moves forward, "these Forests wouldn't exist without all the pain", he sums up simply.

Reflections of an extraordinary existence and an unusual pandemic context, these landscapes with lost edges, fantastical, confound. Defy understanding. Carry the joys and dramas, both intimate and universal. And overwhelm. Because there's nothing closer to human beings than forests," he concludes. They are every moment, autumn, winter and spring. They are wind, noise, emptiness, fullness, song... They stand. They try to hold on..." "Because the seasons must pass and life must prevail," adds her daughter Clara, Clara Ysé, author and musical prodigy, in poignant affinity. "Les Forêts brisées is you. My father. The ones that bloom despite the storms. (...) So powerful in their savagery. I look at them and breathe a little wider."

Anne-Sophie von Claer

Le Figaro - October 2021